Chatgpt finds a hidden crypt

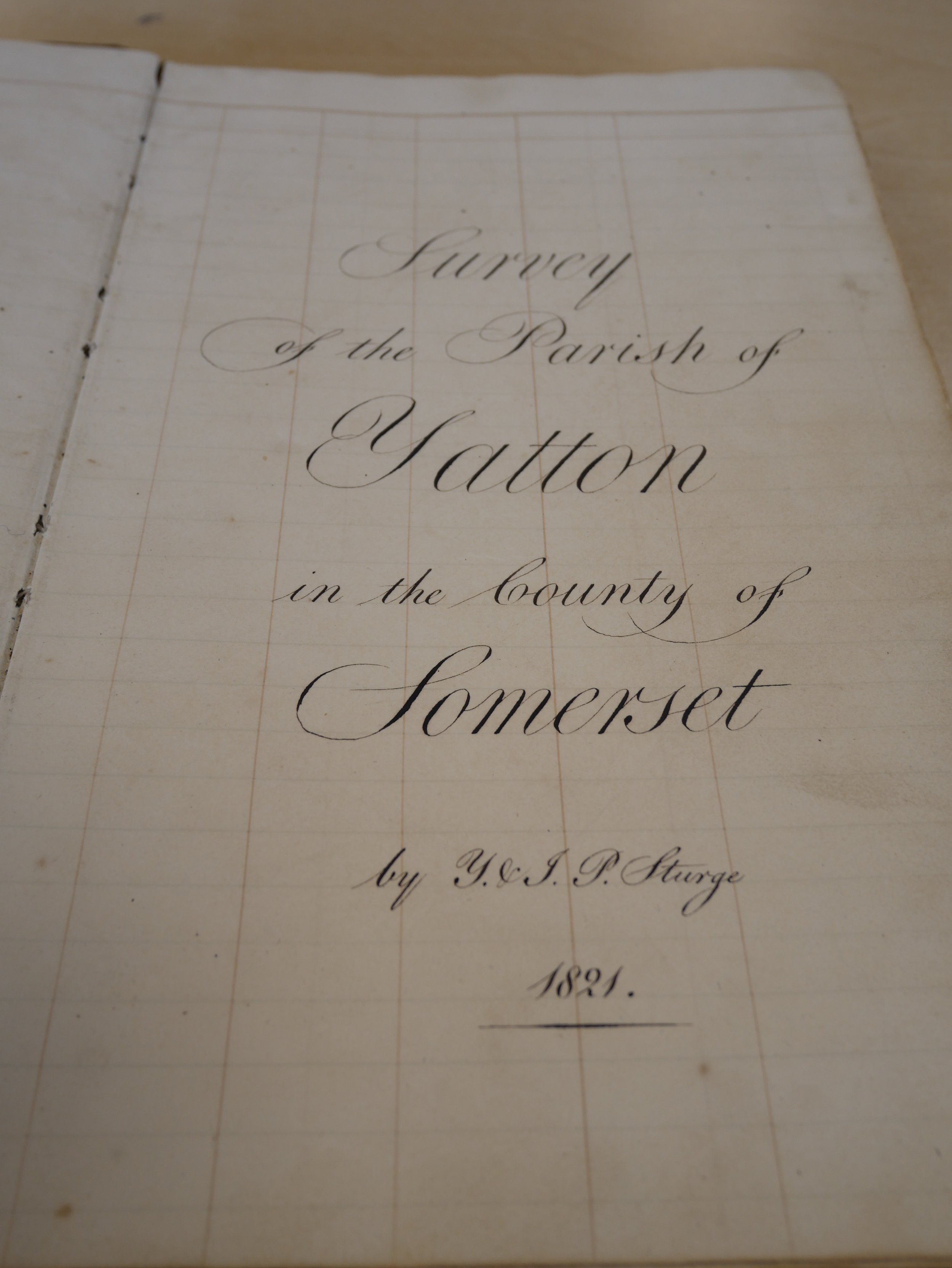

An antique Victorian golden locket that once belonged to thirteen-year-old Sarah Wornell took me on a journey to England, The locket tells the story of two closely bonded sisters in the 19th century — Sarah and her older sister Jane. Inside, beneath a lock of fine blonde hair, is the delicate engraving: “In Memory of my dear Sister Jane Wornell.” Her birth and death dates read: November 20, 1814 – November 1, 1833. A search through the Parish Register of Congresbury, County of Somerset, revealed the first clues. The two sisters lived in Yatton, Somerset. I decided to take the locket back to where it once belonged.

With the golden locket safely in my pocket, I traveled to Yatton, wandered the narrow streets of rural Somerset, searching for traces of their lives. Near the village church, I found the house where the two sisters had once lived. The Wornell family home, known as Causeway House, stands as a fine example of 17th-century architecture with its thick stone walls, large inglenook fireplaces, and exposed oak beams. It exudes the quiet charm of an English country home that has witnessed centuries of laughter, prayer, and loss.

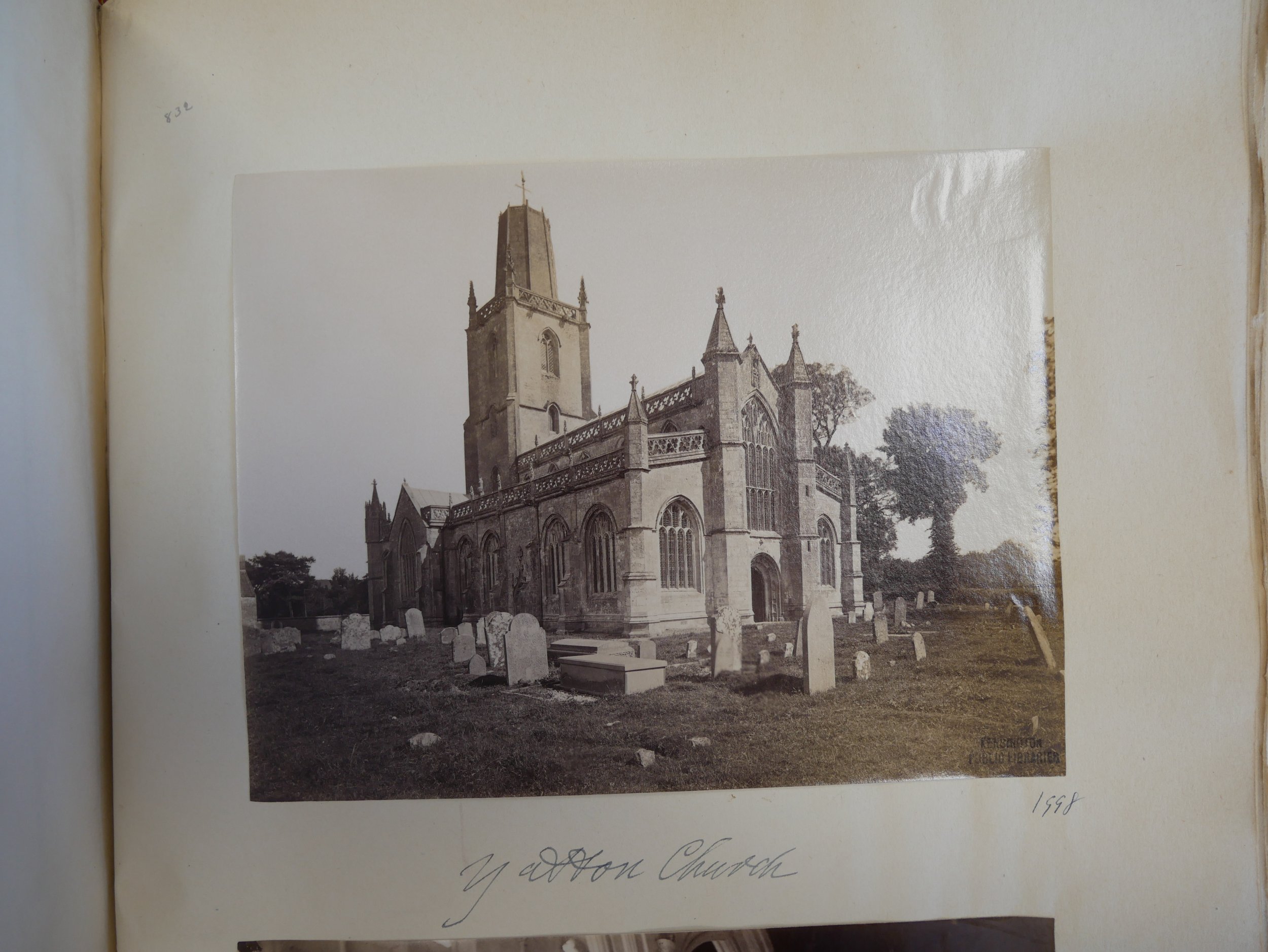

But my search for Sarah and Jane’s final resting place had only begun. On Sunday morning I joined the local congregation for their sermon, witnessing a baptism and hearing the familiar rhythm of hymns rising to the wooden rafters — just as Sarah and Jane might have heard nearly two hundred years ago. After the service, I joined the ladies of the parish for tea, and soon we were laughing together about what had brought me there: a German woman arriving in their quiet village with a golden locket and a story of two forgotten girls. Then one of the elderly women looked at me and said, “I’m not superstitious, but I think there’s a reason why this locket brought you here here. We’ll find out why.” Her words gave us chills, and none of us spoke for a while. After tea I strolled around the graveyard outside. Reading countless gravestone inscriptions without success, I decided to visit the Somerset Heritage Center for further information.

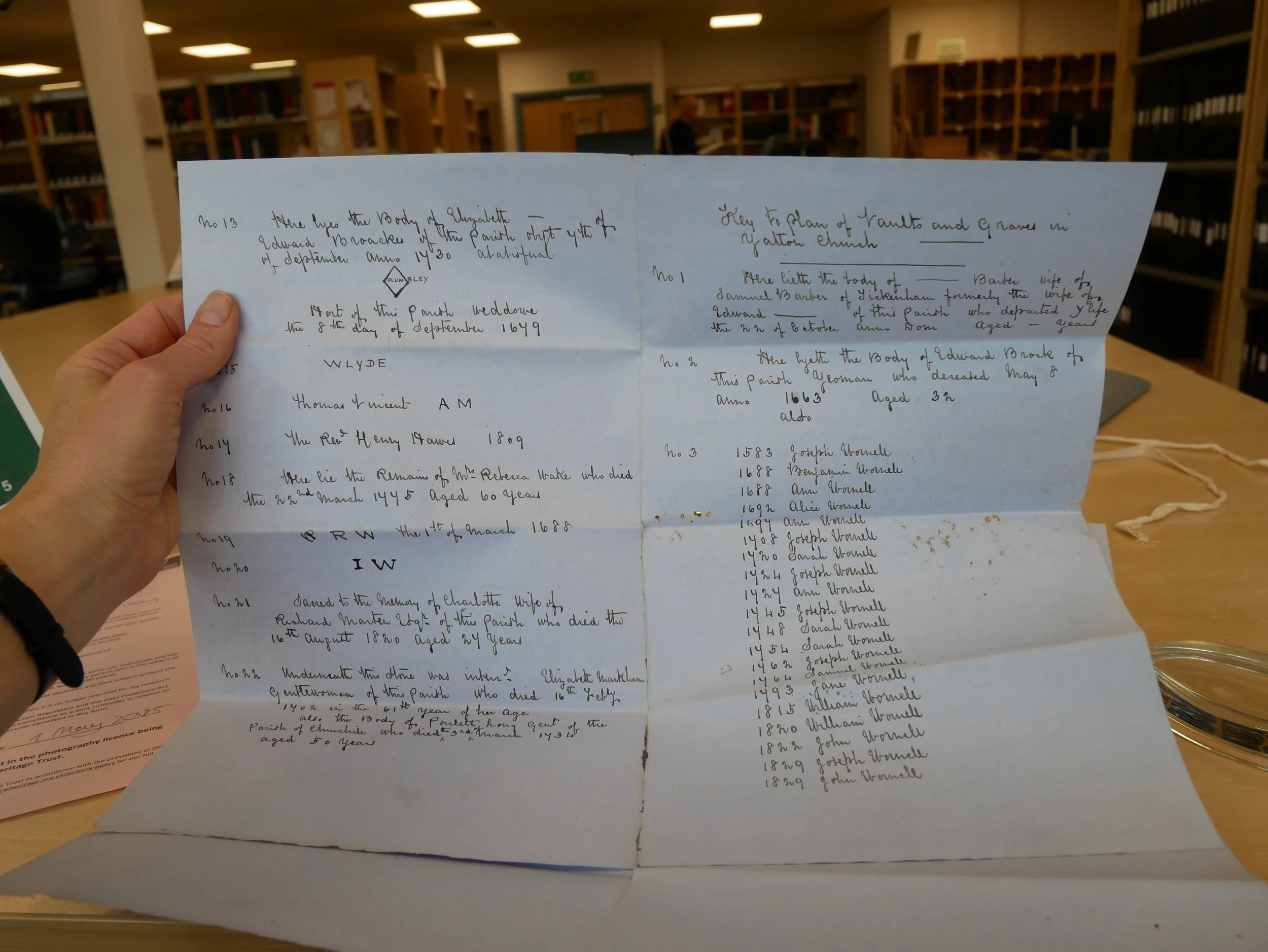

jackpot at the Somerset heritage center

Among stacks of documents and the smell of old paper, I came across something that made my heart skip a beat: a large, time-stained, handwritten document titled “Key to Plan of Vaults and Graves in Yatton Church.” It was proof that the church once had a crypt. As I carefully unfolded the paper, I could see names and numbers scrawled in faded ink. My eyes froze when I reached Vault Number Three: the Wornell family vault. Joseph Wornell had been the first to rest there in 1408, followed by generations of the Wornell family, including William, John, and Joseph — brothers and father. In Vault Number Four were listed Jane, who died in 1833; Sarah, who passed away only two years later; and their mother Betty, buried in 1863 — the last of the family to be laid to rest in the crypt. The paper was brittle, full of holes, smelly and the dust made me cough, but the sense of discovery was overwhelming. The Wornells were still here, not in the graveyard, but beneath the church!

When I returned to Yatton with the news, the two ladies from the local history society and I turned into detectives overnight. I was determined to find the crypt. Even the pastor of St. Mary’s Church was astonished when we told him. “I didn’t know there even was a crypt,” he said, shaking his head. On a Tuesday the church assistant unlocked the church for me, as it was closed to the public, and handed me the key. “Take your time,” she said. “Lock it from the inside so no one disturbs you. Just drop the key off when you’re done.” I nodded, and then I was alone — inside a centuries-old church, the air heavy with silence and time.

Inside the church

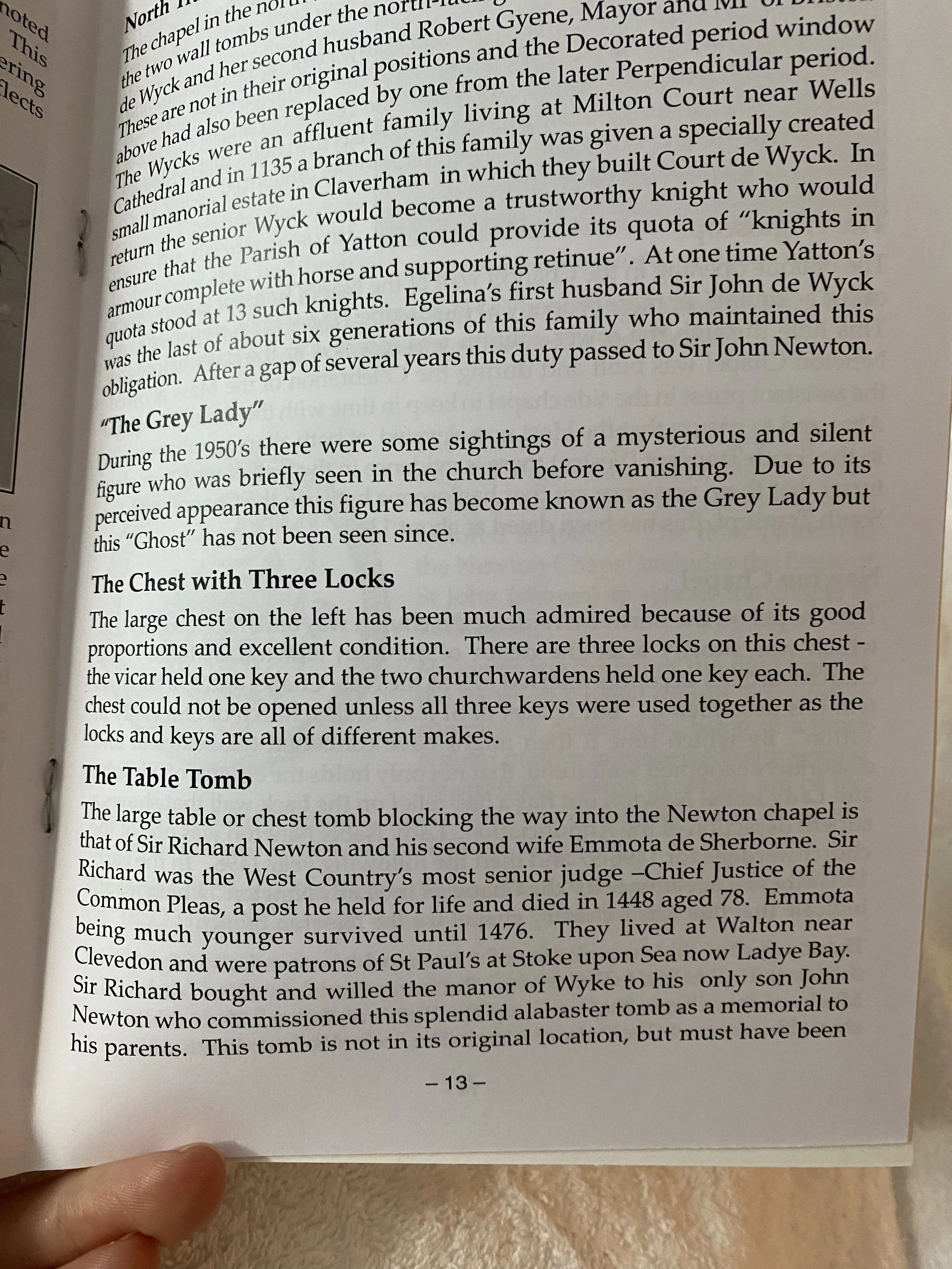

I sat down on one of the wooden pews, the golden locket warm in my hand, and looked around. The church was dead quiet. I opened a booklet about its history which was displayed on the information table at the entrance. It was full of detailed notes, yet nowhere did it mention a crypt. Only one passage caught my attention: “During the 1950s, there were sightings of a mysterious and silent figure who briefly appeared in the church before vanishing. Due to her appearance, this figure has become known as the Grey Lady, though she has not been seen since.” I swallowed. Locked in a church alone — with the Grey Lady for company, I laughed.

I began to walk slowly, my footsteps echoing on the stone floor. I read every wall inscription and every plaque to find a hint of the crypt. One memorial mentioned the Markham family, whose members “lie in the family vault near this place.” Near this place — but where? I continued searching until I found a floor tile dedicated to the Tucker family, a name I recognized from the old vault list. I knew I was close. Exhausted, I sat back down on the pew and took out my phone. Desperate for a clue, I opened ChatGPT and entered everything I had: the church’s name, its history, a picture of the floor plan from the archives, the known reconstruction works. Then I asked: “Where would the entrance to the crypt likely be?”

The answer appeared almost immediately. “Based on the architectural drawing and standard medieval church layouts,” it read, “look closely at the north transept. There is a rectangular marking just below and slightly left of the center. It resembles a trapdoor or stair hatch, consistent with known vault entrances. Would you like a marked version of the floor plan with the possible entrance highlighted?” I replied, “Yes, please.”

can AI find the crypt entrance?

A few seconds later, my phone lit up with an image — the same floor plan I had uploaded, now with a red marking. My heart raced. I stood up, made my way to the north transept, and scanned the floor tiles one by one. And there it was. A large stone slab that was not mortared together with the others. Instead of neat joints, it had a small edge — the slab was loose. On the left side, a small oval hole broke its surface. I knelt down, ran my fingers along the cold stone, and knew I had found it: the hidden entrance to the forgotten crypt.

Right beside the slab was a small section of beautifully tiled mosaic floor. One tile caught my attention — it bore the Latin inscription: Non Omnis Moriar. “Not all of me will die.” I stood there for a long moment, feeling the silence of the church around me. The words resonated deep within me. Perhaps that was the message Sarah and Jane wanted to send. That even in death, they are not entirely gone. That through a lock of hair sealed in a golden locket, through the whisper of archives and stone, they still reach out from the underworld of the dead to the living — reminding us that memory, like love, never truly dies.